Heidegger in the fields of Eastern Europe

20 June 2016

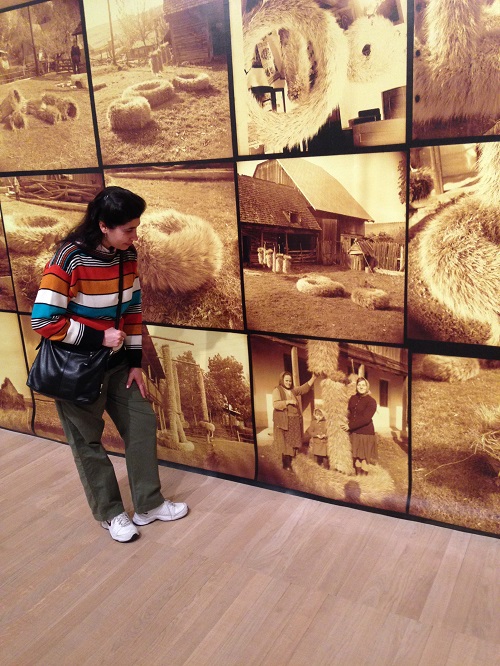

There are many surprises amongst the exhibits at the New Tate Modern, ranging from soap bubbles and sculptures made of couscous to blank walls and capsules to lie in; what they all have in common is a certain extravaganza – one way or the other, they push the boundaries of what we call modern ever further and further. To me, the real surprise is a gaze into the past. An exhibition by the Romanian artist Ana Lupas brings together images and installations of items and materials from rural Transylvania, as it was half a century ago: wheat, cotton, wood and clay are the main characters in a display of ochre and grey.

It has taken the artist and her team over forty years and several alterations to reach this stage in her project, titled The Solemn Process. Initially focused on the annual production of large wheat wreaths (produced in the countryside by a group of villagers), the project soon became a restoration project, because the original structures started to deteriorate due to the vulnerability of the main material used – wheat. So the wreaths had to be encased in metal structures, in order to be preserved.

This is what we can see now, in the Switch House building – a display of large, grey structures, cold on the outside, but warm on the inside, as they cradle forty-year old wheat wreaths from the Romanian countryside half a century ago. From a long-forgotten land somewhere ‘beyond the woods’ (the name comes from Latin ‘trans’ and ‘silva’, forest), crushed by the horrors of the communist regime, Transylvania suddenly shows itself as a mirific landscape and home to warm, self-sufficient and family-oriented people. The range of utensils from the photographs on display would certainly inspire Heidegger to write another volume on the Origin of Art; the wheat wreaths would be right up there, next to Van Gogh’s peasant shoes. But he might keep the title, as there is certainly solemnity in this process of recapturing the past, through a combination of what is ‘ready-to-hand (the equipment – metal, boards, camera) and the ‘presence-at-hand’ that pertains to the human being. A whole new world opens up between the beholder and a few instruments from the past.

Liked your take. Quite apposite in terms of Milbank and Pabst (2016) on return to past of community. I also liked the story: listening to peoples’ stories is a major way. Real experience. In the latter, the point about the English secret weapon, real multiculturalism and creativity thereby said it all.

Heidegger was the banner, so I had to refresh as an ex philosophy student! Especially as I have recently been into Karl Rahner, who was the key mind (a Jesuit) behind Vatican II. As heavy going as Heidegger – gave up on text as resorted to a great study by another Jesuit. I have one of his poems if you are interested. Like (and even more than) art, poetry is prayer and the soul and heart on fire and like the burning bush not consumed.

Some points resonated, in relation to the Origin of the Work of Art, especially:

• The Sublime: awe and reverence about earth and the mystery of the same: God’s creation. That which exceeds our power fully to apprehend. The iceberg idea.

• Then I “got it” on the hermeneutic circle when mentioned is the divine circularity: how not to get around it but to break into this. This is very Ignatian in terms of the idea of “dance”.

It was not therefore surprising later on to see key influences has been Duns Scotus, Heraclitus, Eckhart, Kierkegaard, Augustine. First two were key influences on Jesuit poet GM Hopkins and Franciscan Richard Rohr.

Milbank, J & Pabst, A (2016) The Politics of Virtue: Post-Liberalism and the Human Future. Rowman & Littlefield International