Royal meditation

12 March 2016

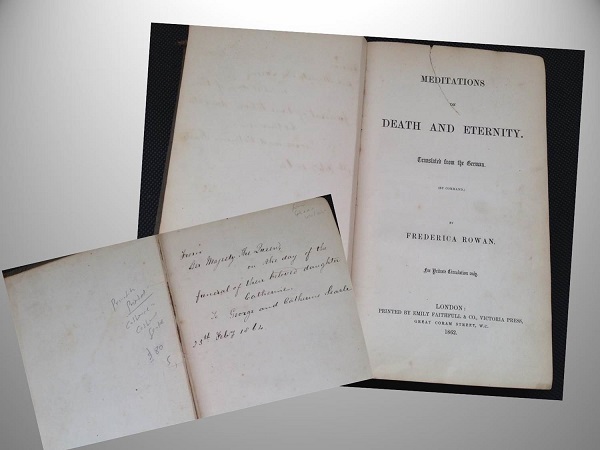

It’s been years now since I gave in to my passion for old books, which almost feels like a vice, if you consider the opportunity costs involved. In one of my regular, guilty trips to Cecil Court, I discover a copy of Heinrich Zschokke’s Meditations on Death and Eternity, from a limited royal edition – “for private circulation only”. It is a translation of sections from the original work Stunden der Andacht (Hours of Devotion) and it was published at Victoria Press (London) in 1862, at the request of Queen Victoria, in memory of her husband, who used to read it frequently. His Royal Highness the Prince Consort had died prematurely, of typhoid fever, in December 1861. The dedication says that these sections “have been selected for translation by one to whom, in deep and overwhelming sorrow, they have proved a source of comfort and edification”.

The book was translated by Frederica Rowan, who also translated, incidentally, The Life of Schleiermacher (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1860), the 18th century hermeneutic theologian who explored the common grounds between Christianity and modern metaphysics (Kant, in particular). Just like Schleiermacher, Zschokke was born in Prussia – but he spent most of his life in Switzerland. And again, just like the hermeneutic scholar, he was also concerned about society, to the extent that he made a career in the civil service – as a representative of the Prussian government in Switzerland. Once he retired from public life, he spent seven years writing his devotional meditations, which were published in over 20 editions and widely read.

The most striking feature of this work is its simplicity – which could also be seen as the reason why it became so popular. To quote just a few chapter titles: “Is slow decline or sudden death most desirable?”, “Fear of death”, “God is love”, “Why must the future life be hidden from us”, “A joy in the hour of death”, and “Thoughts at the graves of those we love”.

That a royal family would dwell on such meditations and find consolation in them cannot but fill one with awe. That a queen or a king would frequently wonder, with Zschokke, “what is the destination of man?” and “what is the purpose for which God called me into being?” (pp. 166-7) could inspire our own spiritual development. Just as the very fact that royals would spend so much time reflecting on death and eternity might.

I think it is an inherent human trait to ponder what happens after death. Similarly, royalty must be incredibly well educated and familiar with a variety of areas. This being said, it would seem only natural for royalty to ponder the meaning of existence. The simplicity of Zschokke’s work is what interests me. I personally find beauty in the subtly simple. Texts that are easily accessible, and yet artfully articulate are those that speak to me the most. To combine this writing style with the infinitely relatable idea of death sounds like a perfect writing choice to me.